Finnish and Swedish accession to NATO would entail several geopolitical endeavours, which could possibly prohibit Russian access to international waters through the Baltic Sea, along with exposing critical infrastructural vulnerabilities in Karelia

After the start of the Russian-Ukrainian war, many neighbouring countries have started to fear Russian interventionism, amongst these, Finland and Sweden. As a consequence, both countries have formally requested to become NATO members in mid May 2022.

The political narrative of Russia has always been against NATO enlargement in Eastern Europe, a region considered to be part of the post-Soviet space and thus of Russian influence. Since the end of the Cold War, all Russian efforts, including the escalation of tensions with Ukraine in previous years, have been aimed at preventing the organization’s expansion. However, the war with Ukraine seems to have accelerated this process instead of slowing it down.

Finnish and Swedish accession to NATO would entail several geopolitical endeavours, which could possibly prohibit Russian access to international waters through the Baltic Sea, along with exposing critical infrastructural vulnerabilities in Karelia, a passage region towards the highly nuclearized artic peninsula of Kola, offsetting the geopolitical balance of the region and compromising Russian security.

Russian-Finnish rivalry and the importance of sea passages

From a Finnish perspective, the war in Ukraine is a repetition of history. Both Finland and Ukraine were part of the Russian empire and both gained independence after the 1917 revolution. However, a peculiarity lies between the two wars, as a matter the fact, in 1939 Stalin decided to invade Finland on the pretext of liberating the population from Nazism (a famous propaganda poster of the time shows a dog barking and says: “the fascist dog barks”).

This narrative is considered to be one of the justifications for Stalin’s decision to invade Finland, beginning the winter war. The winter war is an important part of Finnish history and culture and it is still strongly perceived today as an act of heroism aimed at repelling a foreign invader. Due to the importance of the conflict in 1939 and of how strongly it impacted society, to this day, the Finnish army has amongst its ranks ski soldier regiments and has a very militarily prepared population and infrastructure; the same holds true for Sweden. If Finland hadn’t resisted the invasion, it is likely that the Soviet Union would’ve annexed it. Instead, it transformed into a buffer zone with the Finnish-Soviet treaty of 1948, which gave the country the status of neutrality.

The human cost of the war was very high and Finland had to renounce to parts of its territory like the northern territories and a big part of the southern Karelia region, now a part of Russia. However, regardless of the human cost, from a Finnish standing the resistance was a just and a necessary decision since it brought about, through a free economy, high economic and well-being standards rivalled only by other Scandinavian countries. The same cannot be said for the portions of territory that Finland lost which today do not enjoy the same level of GDP per capita, life expectancy and equality level.

In any case, ever since the 1948 treaty, Finnish policy has always aimed at co-existing with its neighbour and has always been in favour of not provoking Russia by acceding to NATO even if it would’ve meant renouncing to being shielded by article 5 of the alliance. Finnish policy has preferred to follow what came to be known as “finlandization”: enjoyment of favourable relations both with the west and the east while remaining neutral. However, that policy has fundamentally changed with the Russian-Ukrainian war of 2022.

The strategic importance of sea passages

With the war in Ukraine, security threats have been placed on countries confining with Russia that had previously carried out a role of being “buffer States”. The military security of these countries has been put into question as Russian foreign policy has become militarily active. As such, as naturally happens in international relations, at each action that offsets the geopolitical balance, another action to rebalance the latter must be put into place: Finland, a formally neutral country, along with Sweden, have both formally requested to join NATO in May 2022.

Finnish and Swedish accession to NATO would change the geopolitical scenario of the Baltic Sea and would create a new pole of military strength in the alliance.

The strategic relevance of the region is vast as both Finnish and Swedish populations are well organized in the event of war. Both countries have active wartime shelters in great numbers, in fact, in some Swedish regions it is mandatory for each house to have its own bunker, while in Helsinki alone there are over 5000+ bunkers. In addition, both countries have well-equipped armies that are adapted to NATO requirements.

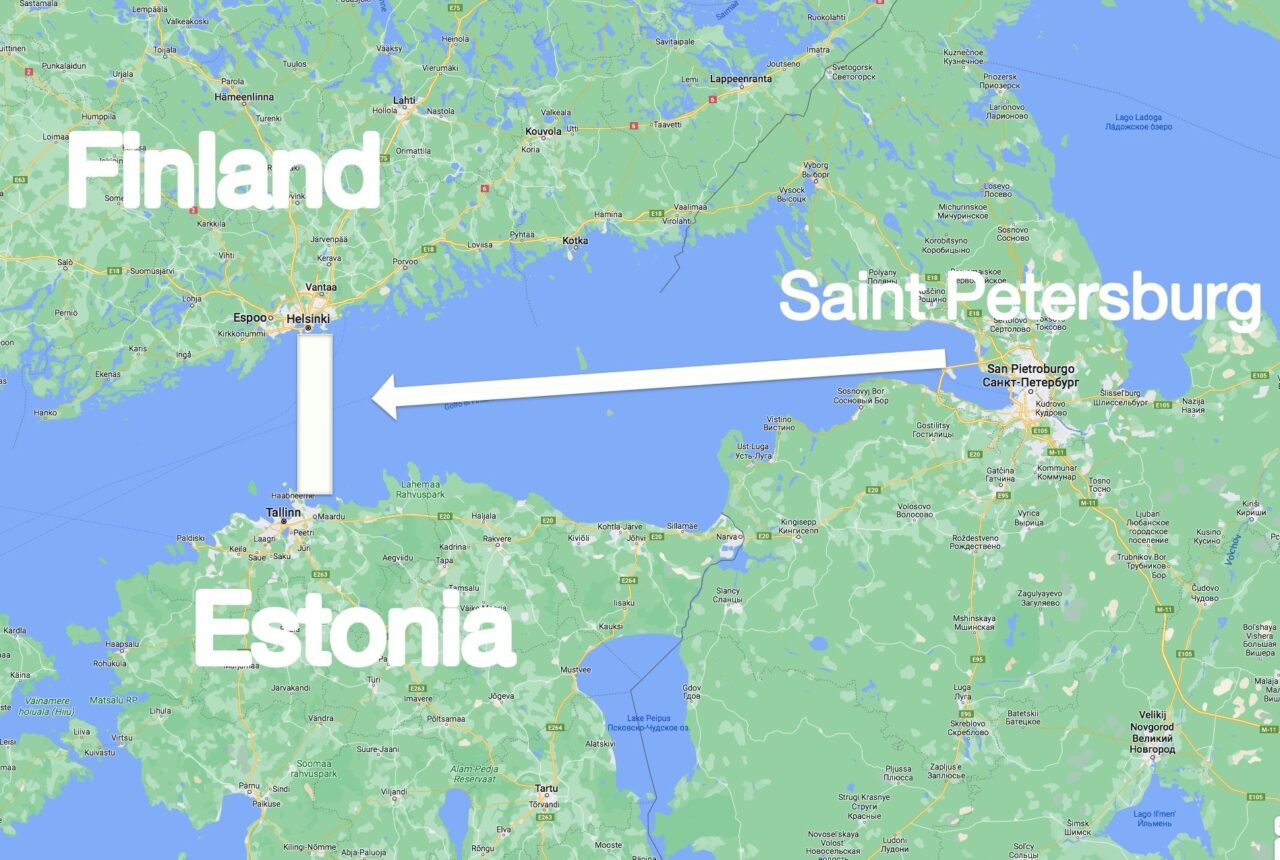

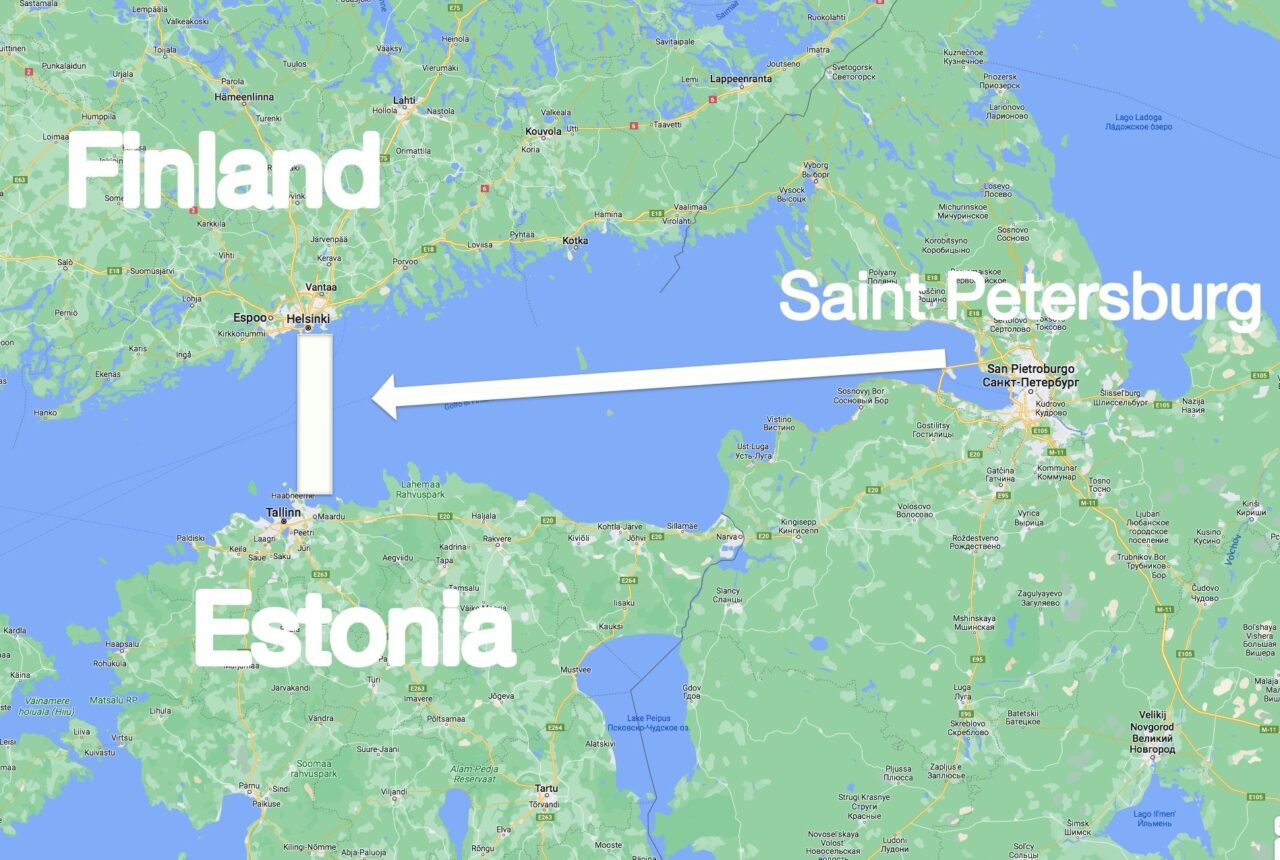

However, the greatest strategic relevance of these two Scandinavian countries lies within their geography. With Finnish accession to NATO, Russia would have it’s maritime passage from Saint Petersburg to international waters monitored by two of the organization’s member states: Finland and Estonia. As a matter of fact, the maritime distance between the two countries would be enough to make sure that no Russian ship would be able to pass through the Baltic Sea without being detected. From a legal standpoint, the maritime boundaries of countries, established with the Convention of Montego Bay (1982), are made up of two layers: territorial waters (12 nautical miles from the lowest costal sea-line level), where States can carry out their traditional powers, and a contiguous zone (another 12 nautical miles, thus bringing the total boundary to 24 nautical miles), where States have limited powers that mainly regard the security of the continental land. Thus, the two maritime borders of Finland and Estonia, which in some points reach 40-50 nautical miles of distance, would be so close that if they were to both be part of a defensive alliance such as NATO, they’d be able to block off their maritime territory to Russian ships.

Such a scenario would substantially void Saint Petersburg of its access to the sea limiting the strategic importance of its port. The only ways Russia would have left to access the sea from the western side of its country, would be from Murmansk, through the arctic route, from the Black Sea through the Bosporus strait, or from Kaliningrad, which however is a Russian exclave with no connection to mainland Russia.