Poland is now in the forefront of the counter-offensive to Putin’s Russia. The reputation as the troublemaker fades into the background, as the country becomes the linchpin of the West’s response to Russian aggression against Ukraine

Back in 2017, the nationalist and Euro-critical nature of the Polish government made it one of the biggest supporters of newly elected President Donald Trump. The same cannot be said for the arrival of the Biden administration, which has certainly not aroused the same sympathy, but the Russian invasion of Ukraine really acted as a game-changer.

Warsaw has not only announced that it will increase its military spending from 2.2 to 3% of its GDP, well above NATO’s recommended 2%, but has also increasingly fortified the eastern flank of the Alliance with the help of the Pentagon: the number of military personnel deployed in the country has more than doubled, and so has the amount and types of military equipment and capabilities positioned in the country. At the moment, Poland is also a special hub for transporting military equipment to Ukrainian armed forces, as well as a staging post for weapons, ammunition and fuel.

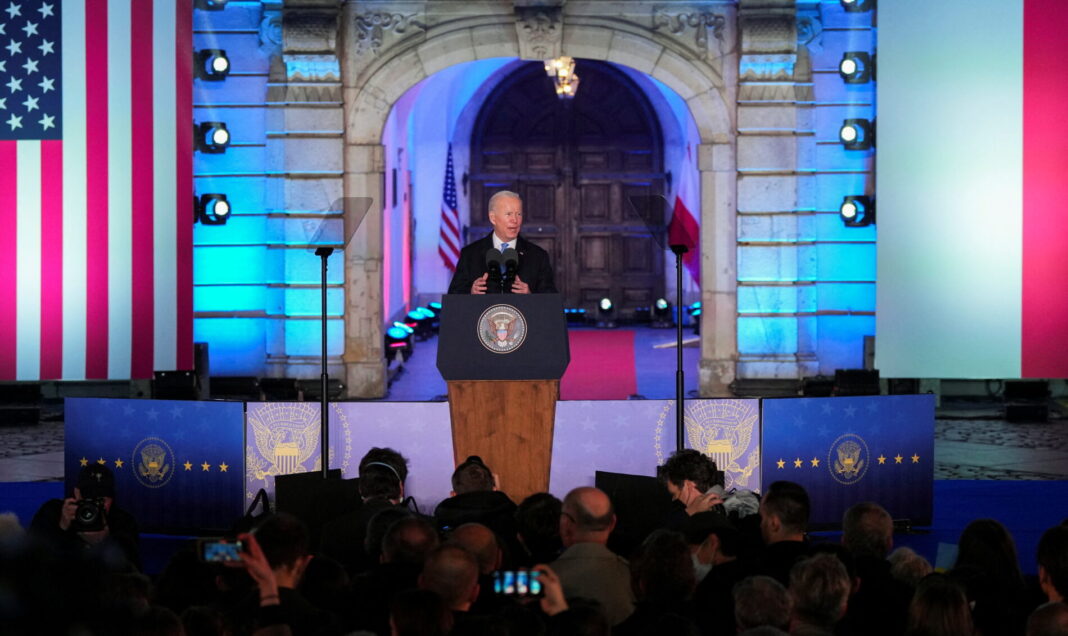

Within a month, Secretary of State Antony Blinken, Vice President Kamala Harris and more recently President Joe Biden himself have visited Warsaw. This signals a distinct change in relations between the two countries: Poland has become a key NATO ally and a strategic partner in the region for the United States.

Interesting to note how Poland’s strengthened position within NATO and the EU has even prompted the country to propose itself as a substitute of Russia within the G20, following the US and its Western allies’ proposal to expel it from the platform.

Pushing for tougher measures

Poland is at the forefront of the counteroffensive to Russia, but its action is not limited to supporting sanctions in place. The country is working to cement a bloc of European countries, among which the Baltic States and the Czech Republic, that are pushing for even tougher sanctions. The long and painful experience under the Russian game is in fact contributing to the formation of a true Eastern front of which Polish President Andrzej Duda intends to be the spokesman.

The designated target currently appears to be the oil & gas sector. Being the biggest revenue to Russia’s budget, energy is considered the only compartment that, if damaged, can convince the Kremlin to withdraw its troops from Ukraine. However, discussions will be heated: the embargo is likely to be resisted by many countries that are highly reliant on Russian imports, such as Germany and close ally Hungary.

Disagreements with friend Hungary

An alliance that had never given signs of abating, not even with the harshest warnings from the European Union, seems instead at risk as the Russian aggression against Ukraine continues.

On one side Poland, immediately siding against the Kremlin and pushing for tough sanctions, on the other Hungary, Putin’s closest ally in the EU, struggling to maintain neutrality since the first days of war. If the two Visegrad countries have always shared values and policies, making almost a common front against the demands of Brussels, the war in Ukraine seems to have broken this idyllic balance.

Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán has condemned the invasion and opened the border to Ukrainian refugees, but he has long thwarted the European counteroffensive, opposing energy sanctions because of the country’s dependence on Russia, and not only refusing to send weapons, but also blocking their transport from other countries through his territory.

At the moment, Hungary is the only country that seems to be moving against or at least not in the same direction as the European bloc, once again confirming – unlike Poland – its reputation as the inveterate troublemaker. Only time will tell what effect this will have on Hungarian—Polish relations, but also what will be the consequences for the ruling Fidesz party, that is due to face national elections in the upcoming days.

Open-arm welcome for refugees

When it comes to people fleeing war, Poland hasn’t exactly been known as one of the most welcoming countries. The government of the national-conservative Law and Justice (PiS) party has often stood out for its heated anti-migrant policies. Just a few months ago, hundreds of refugees from Afghanistan, Syria and Iraq poured over the Belarusian border trying to enter Europe, but Poland made its position very clear by erecting a barbed wire fence and strengthening its military presence along the border.

With the Russian invasion of Ukraine, incredible numbers of people poured into neighbouring countries in search of safety, triggering the largest refugee crisis since World War II, but this time Warsaw’s reaction was markedly different.

No troop deployments or erection of walls, no water cannons or tear gas, the war next door has caused a distinct change of heart in PiS Poland: emergency shelters are quickly being set up in gyms and stadiums across the country; train stations are filled up with donations; refugees receive food and water as they arrive and are also offered free rides to wherever they wish to go.

However, why is Poland showing us this new and unseen face? The factors influencing Poland’s behaviour are multiple. The racial one is undeniable: journalists have reported numerous cases of discrimination against African or Asian students who were also fleeing Ukraine. In addition, there are the strong cultural and linguistic ties given by a border that has often shifted between the two throughout history. More importantly, there is one factor that could also explain the other attitudes described in this article and it can be summed up by the question, “Could I be next?”.

With the aggression on Ukraine, the shadow of the Russian threat is once again stretching over Poland, shaking the spirits of a country that has vivid memories of what life was like before the fall of the Berlin Wall.