In an increasingly unfertile Europe with more pensioners than people under 30, who will invent, study and introduce fresh ideas?

Ulrike Bischop is a young pastor in Dessau, Saxony-Anhalt. This is where she was born and was given her first post after earning a degree in theology and years of work experience. This is where she celebrated her first christenings of two children. One was Afghan, the other Iranian. She is very emotional about it, but she’s not too surprised by the two little protestants who arrived along the eastern migration routes to the town of the Bauhaus. Like the other Länder in what was once East Germany, Saxony-Anhalt has experienced a demographic shock since unification that has affected the whole of the former DDR. A dramatic bottoming out of births, a textbook case for demography experts. Less births in the ’90s, means less women of childbearing age today. This hasn’t just happened in Dessau, or in Eastern Europe alone. But this earlier minor shock in Dessau and these recent christenings provide an indication of how demographic dynamics are both predictable and unpredictable.

There are long-term effects that span entire generations. We already know that 222,418 little girls were born last year, who in 2050 will reach the age when women, on average, have their first child. There are cultural, social and political changes involved. Ulrike’s mother, in East Germany, had more children than her children in a unified Germany; only one Italian woman in 10 born in the 1950s didn’t have at least one daughter, while 22% of women born in 1977 had none. And then there are the sudden historical reversals – a fallen wall, a war, a climate disaster. In other words, demographic forecasts have to be taken with a pinch of salt. Yet the general trend in Europe over the long term is clear: at the start of the 20th century, every fourth inhabitant in the world was European, but in 2050 that ratio will be one in 14. From here to 2050, European Union growth will be close to zero (20 million or so, plus 3%), while Africa’s population will double.

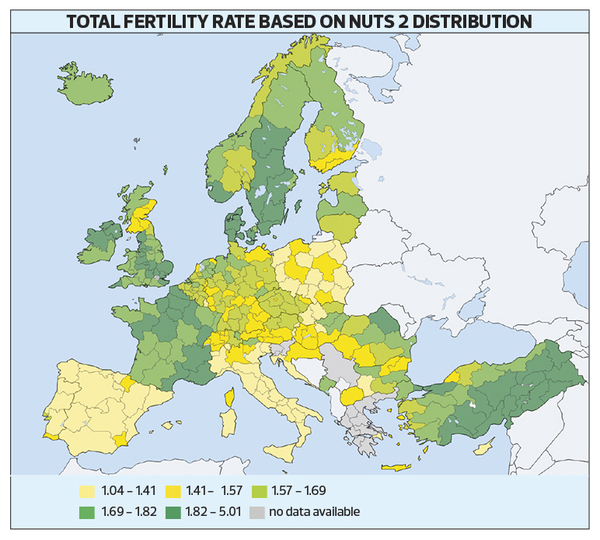

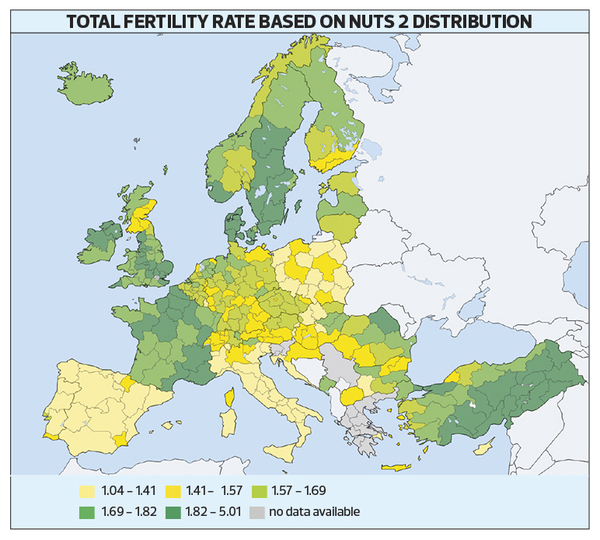

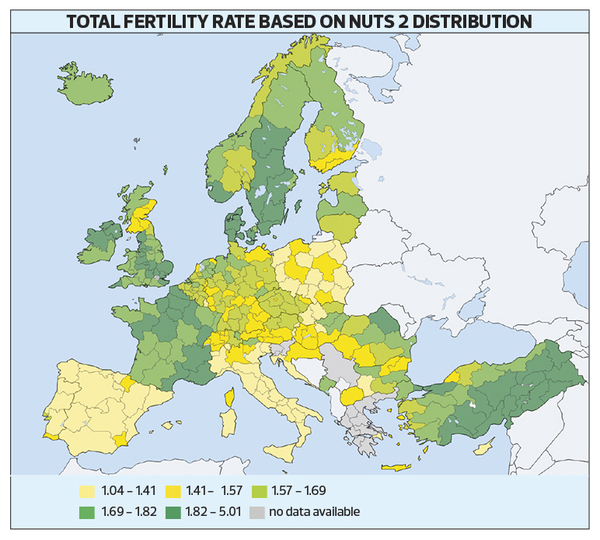

A few weeks ago, the Lancet magazine published a weighty study on the world’s population and fertility. The researchers used a vast and uniformed database covering 195 countries between 1950 and 2017. First fact: over that timespan the fertility rate in the world has halved, from 4.7 to 2.4 children per woman; during the same period the population has almost tripled, from 2.6 to 7.6 billion. Second fact: the number of children per woman has dropped everywhere, more or less, yet there’s a huge difference between the minimum (in Cyprus, the fertility rate is 1%) and the maximum (Niger, 7%). Third fact, close to home: the population has decreased in 33 countries, most of which are in Europe. The “replacement” fertility rate – meaning the rate which, given no immigration, guarantees the same population distribution from one generation to the next – generally stands at 2.1 children per woman. No European country meets this target; the EU’s average is 1.6. So it stands to reason that by 2050 the distribution of European population will have changed radically. In absolute terms, the population will continue to grow gradually in total terms (528.5 million in 2050, against 516.6 million in 2020), and drop in certain countries, including Italy, Germany, Greece, Poland and the all of Eastern Europe. Meanwhile, France (plus 6.5 million), the United Kingdom (plus 10 million), Sweden (plus 2 million) and the Scandinavian countries will continue to grow. These Eurostat forecasts are clearly affected by the hypotheses made regarding migration flows. The basic forecast scenario is based on the trends for the last 50 years. For Italy, for example, this method forecasts a drop in population of close to 1.8 million people in spite of net migration of 200,000 up to 2050. For comparison’s sake, in 2017 the known entries were 85,000. But what matters most, alarms demographers and finance experts and is changing social dynamics is age distribution. It will move forward. Taking all the countries of the EU into consideration, by 2050 the population in the 80 to 84 age range will top the 0 to 4 age range. The proportion of the population over 65 will amount to 28.5%. In other words, “we’ll need a workforce of 100 million people”, Stefano Allievi has written in a 27-page booklet outlining what we should know about immigration. In a world with more over 65s than under 30s, Allievi writes that the problem is not just pension sustainability but also the lack of innovation. “Who will be inventing, studying, spawning new ideas?”, the sociologist wonders.

But not all European countries have the same demographic horoscope written in the stars. The graph of age distribution has stopped being a pyramid for some time and is now more of a cylindrical shape with a tapering bottom and bell-tower apex. But there are differences from country to country. Looking back at our ratio of people over 65 against the total population, the European average of 28.5% in 2050 includes top-ranked Greece (36.5%), with Italy in second place with 33.8% and lowest-ranked Sweden with 22.7%. France, which within half a century could overtake Germany in terms of population, by 2050 will ‘only’ have 25.6% of the population over 65. Therefore, when we talk about “demographic winters” – as do Letizia Mencarini and Daniele Vignoli, the demographers who wrote the book Genitori cercasi (meaning “Parent’s wanted”)– Italy is the one shivering the most followed closely by Spain, Germany and Poland. The demographers add that the ageing process will be slower in France and Sweden “thanks to a fertility supported by a greater number of children on average per woman and by a larger female contingent”. In other words, the countries in the south and east of Europe will feel both the effects of the demographic decline, which will result in there being fewer women of birth-giving age, allied with the lower fertility of the younger generations. Mencarini points out that countries with less severe or even mild demographic winters, such as Great Britain that is a case apart in Europe, undoubtedly experienced a decline in the ’80s and ’90s but later made up for it. In these cases, “it was more of a postponement, a shift of the age of the first pregnancy to a later date” due to social, environmental, physical, cultural, economic and political reasons.

And now we come to the politics. In the countries where the hole is still gaping, no systemic policies have been introduced to support young people and births. But there’s one exception that interests demographers: Germany, where ageing and demographic decline have been included in the political agenda. “The German government has allocated considerable funds”, explains Mencarini. But that’s not all. “It’s been a matter that has been up for debate, and this has helped”. Even the economic crisis, which led to the consolidation of the baby recession in southern European countries, didn’t have the same impact here. The fact is that the fertility rate in Germany has risen from 1.47 in 2014 to 1.60 in 2016. “It’s too early to say whether it will last, these dynamics cannot be assessed over just a few years”, Mencarini warns. So social policies can help, provided they are systemic, consistent, don’t change from year to year or are nothing more than empty propaganda – which, on the issue of natality, can easily tread on dangerous ground, with women being blamed and shamed by events such as the Italian fertility day and the rhetoric encouraging women to have children for the sake of the country. The fact is, as demographers warn, that these actions may mitigate but will never reverse a trend that is at this point well-established.

@robertacarlini

You will find this article in the eastwest paper magazine at newwstand.

In an increasingly unfertile Europe with more pensioners than people under 30, who will invent, study and introduce fresh ideas?