Sports car, lowered suspension, leather seats precisely protected by plastic from the factory: traveling alongside those old style Paykan still in circulation, it moves with its rumbling engine in the gymkhana of Tehran traffic.

It is an image that has been representing part of Iran for years: that of the new rich, raised in an environment of a poorly defined opulence, starting from 2009 onwards. While bread and chicken prices were tripling, luxury cars (which cost up to three times more than abroad) and their drivers – the parvenus, sons of an underground economy – thronged the streets of the largest city, catapulted into an unprecedented dimension of wealth never seen until then.

The gap between rich and poor widened, frustrating the middle class hopes.

Iran was crushed by the sanctions, but there were those driving Porsche and Maserati. On the one hand there were the privileged, on the other the less fortunate. In between, an increasingly small and needy middle class struggled to stay afloat.

Those were the years of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s presidency, the months (between 2012 and 2013) when the rial (the Iranian currency) lost 40% of its value, the days when inflation rose between 20% and 40 %, those of corruption scandals, which are now considered “systemic” by some analysts.

What has changed

Those days are now to be considered as history. With the election of Hassan Rouhani in 2013, a pragmatic moderate who is engaged in reforms, luxury cars have not suddenly disappeared from the streets. Yet, something has changed: 1) inflation fell to 9.5%, which is a record in the last twenty-five years; 2) the nuclear deal was signed and sanctions were partly suspended [see EastWest focus here]; 3) Tehran is slowly retaking its place in the global square.

An elitist response to social change?

It is among the lights and shadows of this “great return” that middle class hopes, the target audience of the current president, hide. If the 1979 revolutionaries were mobilized in the name of mostazafan (the oppressed), today Rouhani aims at giving satisfaction to the middle class, which defies any categorization. Furthermore, it is crucial to point out that contemporary middle class is partly the result of an élitist response to the social changes that took place in the 1990s, as sociologist Kevan Harris argued in MERIP journal.

The anti-élite anger and the great “crash”

When, in April of 2015, a yellow Porsche crashed in Tehran’s Shariati Avenue, an anti-elite anger mounted on the web and social media. A woman and a man were in that car. She was from the southern part of the city, known as the poorest area. He was, instead, a “nouveau riche” who had bought the car two days earlier.

Ali Khamenei, the Supreme Guide, claimed against those who, “with their expensive cars”, created “psychological insecurity within the society”.

The actual crash of the middle class was occurring during those days, telling the story of this group of Iranians who have slowly become poor over the years, also as a result of two important factors: labor deregulation and the dismantling of the public sector.

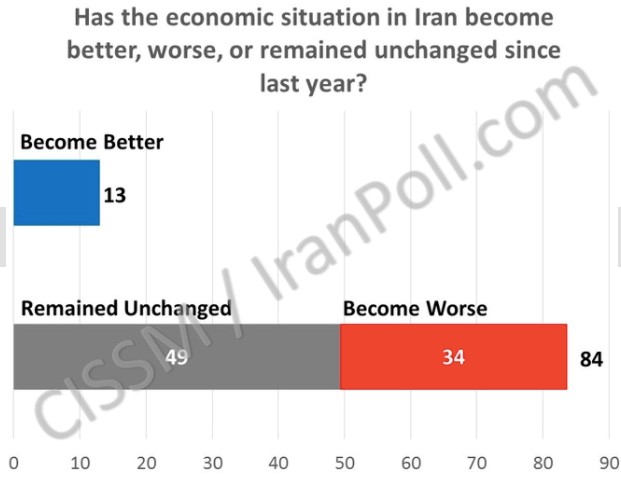

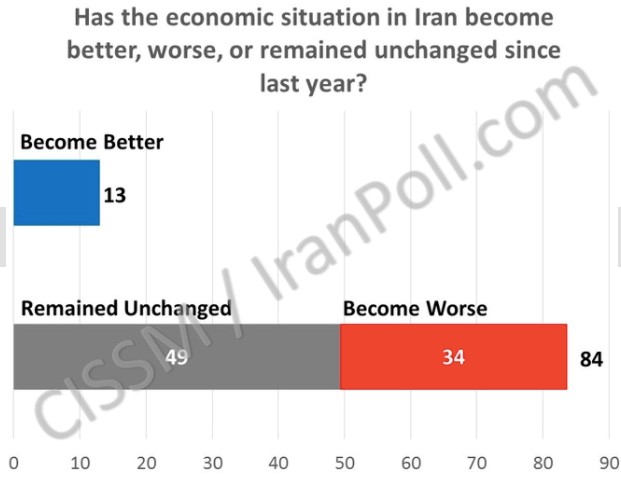

Today, growth prospects are positive: 5% for 2016. In Tehran’s year zero, or in the post-sanctions era, newspapers report about an increasing number of new agreements signed by Iran with other foreign countries. Despite this, a survey made by IranPoll with the University of Maryland, photographed a country which seems to be resigned and discouraged. The question was: “The economic situation in Iran has improved, worsened or remained unchanged compared to last year?” and 49% of respondents answered that nothing has moved on and 34% complained about a negative trend.

Shop keepers, small farmers, students, and employees are still waiting to see the nuclear agreement benefits materialize, in terms of purchasing power and improving life quality.

The election “test” is scheduled for May 2017.

Sports car, lowered suspension, leather seats precisely protected by plastic from the factory: traveling alongside those old style Paykan still in circulation, it moves with its rumbling engine in the gymkhana of Tehran traffic.