Following the lifting of sanctions, Sudanese politics is pushing in different directions to find a solution to the country’s economic crisis.

After twenty odd years of isolation, Sudan has now resurfaced on the international scene, developing its relations with different countries and allies. Among the objectives of this diplomatic choice, there’s no doubt the main one is finding financial support to ward off the increasingly serious economic crisis, partly the result of South Sudan claiming independence, taking with it 75% of its oil reserves, the resource that had always propped up the country’s balance of payments. But the roots of its economic problems are many, date back to much earlier and run much deeper.

Khartoum has always claimed that the main culprit were the sanctions imposed by the United States in 1997, with the country accused of promoting terrorism. Ever since then its diplomatic efforts have constantly worked to remove this provision. If it were lifted its vast debt could be reduced and it might attract new investments, providing some kind of breathing room to its sluggish economy. The sanction revocation process came to completion last October.

This is undoubtedly a major achievement, offset by Sudanese president Omar Hassan al-Bashir signing a number of cooperation agreements the following month with Moscow, which among other things include the construction of a first nuclear power plant, military training, the supply of a few SU-35s, the lasts Russian fighter plan, and much else besides. Russian sources estimate the whole package as amounting to one billion dollars. Then again, it’s common knowledge that in the past the Soviet Union was the main Sudanese military partner. If anything, the surprise was provided by president al-Bashir’s statement which, on this occasion, underlined how its military reinforcement will help provide “protection against the US’s aggressive actions”. He then went on to voice his dismay at American interference in the area and its responsibility for the Middle Eastern crisis as well as the division of his country and the conflict in Darfur. He ended by offering to act as gateway for Moscow in Africa. A speech that openly defied the United States but may also have had an internal political purpose. It may also have been a warning to anyone who might prove to be too pro-American, thus bringing out into the open a leadership conflict that just a few months later, last April, would lead to the dismissal of the foreign minister, Ibrahim Gandour, and a government overhaul.

Even on a regional level Khartoum is seeking to find a tricky balance between the two opposing factions on the other bank of the Red Sea and among the various political and ideological movements within its own country. Once again the reasons are eminently economic. “The main factor on which its foreign relations depend is the situation of the Bank of Sudan”, according to Magda El Gizouli, a Sudanese analyst, referring to the state of the economy in general. Therefore it’s the seriousness of internal economic crisis that has convinced Sudan to cut its decade long ties with Iran by siding with the Saudi led coalition in the Yemenite crises, despite the Saudi’s being one of its main rivals in the region. Sudan has taken an active part in the conflict by sending a few thousand soldiers. In return it has seen a considerable increase in economic support from coalition countries. According to Sudan Vision, a site close to the government, the Saudi aid alone has increased from 11 billion dollars in 2015 to 16 in 2016.

But as the conflict wears on and the Khartoum government’s regional relations develop it might have to decide once again whose side it’s on. The positioning problem began when Saudi Arabia imposed a blockade on Qatar. The reasons are the solid ties between Doha and Iran, which backs the Houthi rebels against the Saudi coalition in the Yemen war. Turkey has stood up in favour of Qatar and has bolstered its military contingent in the country. The Sudanese government has decided to sit on the fence. In fact it has indicated that a consolidation of its relations with the Turkish and Qatari governments is taking place, with which it has a solid alliance, as well as their sharing of the political Islamic ideology promoted by the Muslim Brotherhood.

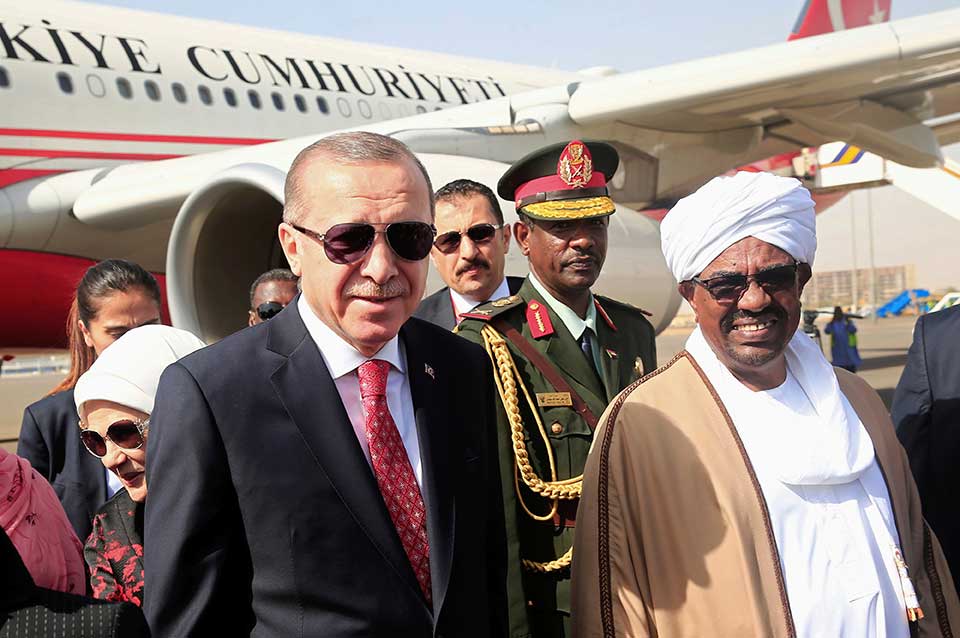

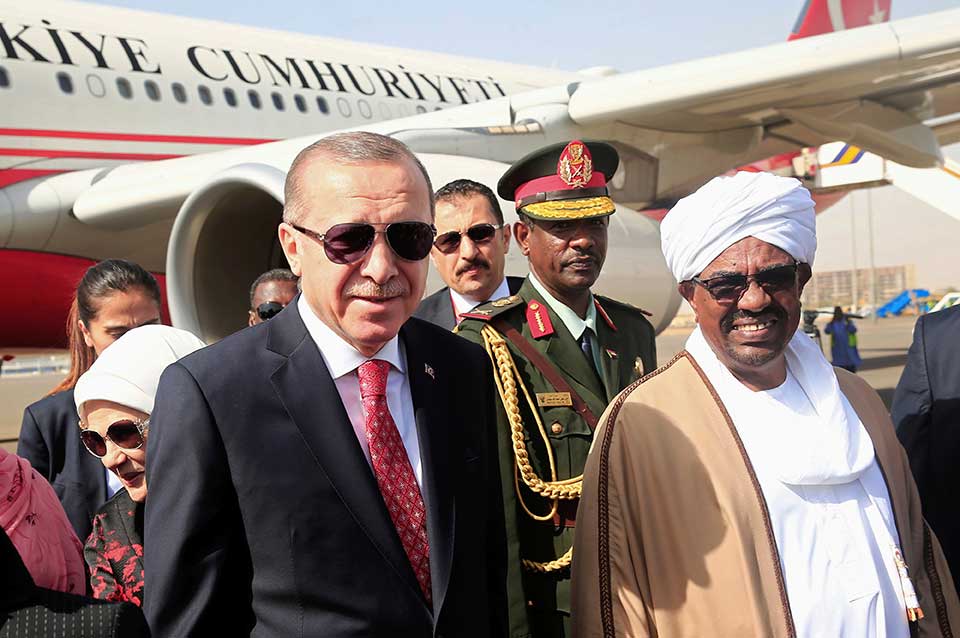

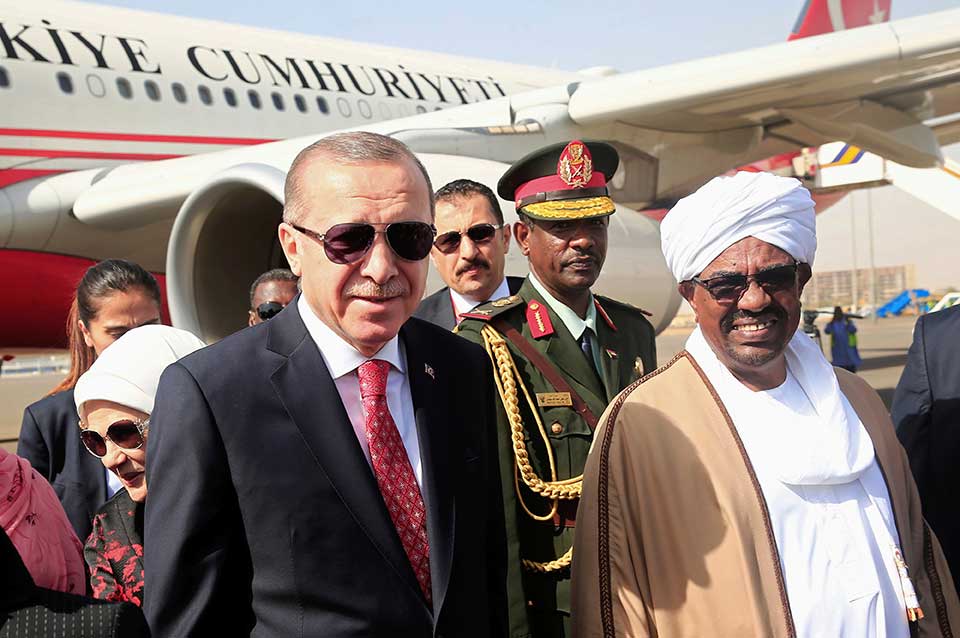

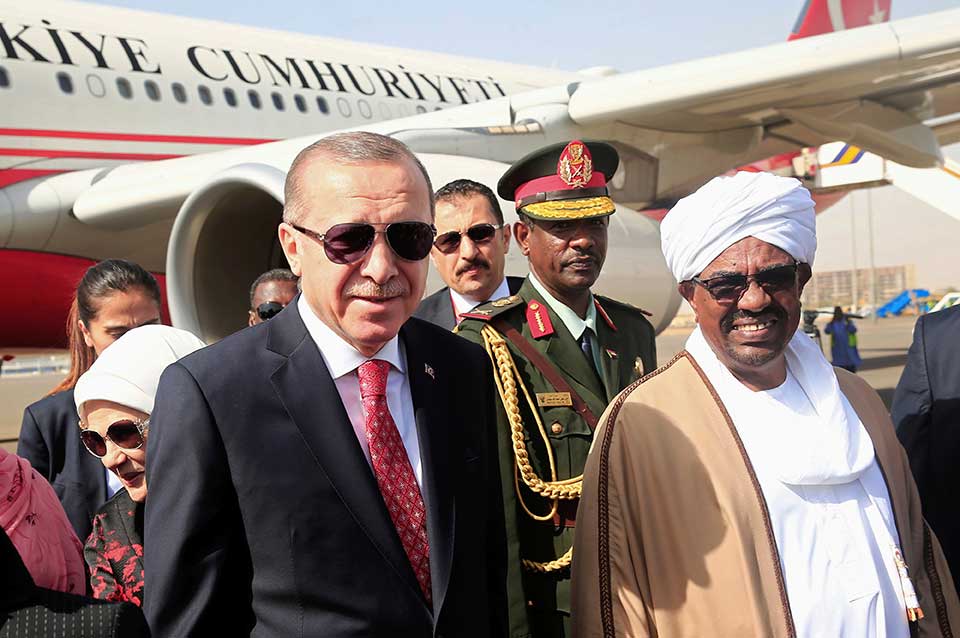

Last December the Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan was received in Khartoum during a visit that the press in both countries labelled as ‘historical’. Among the many agreements stipulated on this occasion one that stood out was Turkey’s concession of Suakin Island, an ancient Ottoman settlement in a strategic position in front of the Saudi coast. Officially, the agreement concerns the restoration of ancient buildings dating back to the Ottoman Empire, but many suspect that the real objective is the beginning of a Turkish military presence in the area. Last March an agreement was stipulated even with Qatar over Suakin. Four billion dollars to develop the port and turn into the second largest in the country, after Port Sudan, which is sixty miles north along the same stretch of coast.

Khartoum’s decisions have raised the level of tension in the area, especially with Egypt, always suspicious of anyone who supports the Muslim Brotherhood, and with Eritrea, which is also an active participant in the Saudi coalition. During the first weeks of the year an increase in Sudanese troops was recorded along the Eritrean border, a circumstance that caused some concern over the possibility of an armed conflict. Then the tension dissipated. But the issue of participation in the Saudi coalition remains.

At the beginning of May the minister for Defence in an audition before parliament stated that participation in the war in Yemen was being reconsidered, especially seeing as Sudanese troops have suffered considerable casualties. Even the opposition closest to the Muslim Brotherhood’s ideology is pressing for the country to withdraw from the agreement. Other rumours say that Saudi Arabia is putting pressure on Khartoum for it to stay. If it is to provide major additional funds, Sudan has to choose sides once and for all. The next months could lead to new developments in Sudan’s complex diplomatic relations and its internal balance of power.

To subscribe to the magazine please access our subscription page here

Following the lifting of sanctions, Sudanese politics is pushing in different directions to find a solution to the country’s economic crisis.