Two years ago on the eve of the Japanese elections, I prepared a guide, published in China Files, to introduce international readers to the Japanese political spectrum.

The situation in 2012

Today, with the new elections for the House of Representatives just days away, once we take into account distinctions such as the exit of the “reckless old man” Ishihara and his group from the Restoration Party, we might as well just stop after the first box.

Organized in record time (parliament was dissolved on 21 November) this election looks set to play out like an episode of the detective series, Columbo: from the outset we already know the identity of the culprit, or in this case the winner.

At the beginning of the 2000s some had hoped that Japan could revolutionize its political system and introduce a two-party system like that in the United States and Great Britain; this was not to be.

The latest forecasts, daily newspapers and opinion pollsters are largely in agreement about the figures, predict that the ruling party looks set to win between 300 and 310 seats out of a possible 475. Such a result would allow Abe’s party to govern alone, without the support of its current conservative coalition partner the New Kōmeitō Party, which is closely linked to the religious group Sōka Gakkai.

The outcome of Sunday’s ballot is poised to result in a House of Representatives that closely resembles the current chamber, with only one standout power: the Jimintō Liberal Democratic Party of current Prime Minister Shinzō Abe.

In reality, this is just a continuation of the Japanese political situation post 1955. The so-called ‘1955 system’ of the outright dominance of the LDP lasted until 1993 when a Prime Minister from another party was finally appointed.

The only party that has managed to get the better of Jimintō during the last 45 years, the Minshutō (Democratic Party) led by Yukio Hatoyama and Naoto Kan, has failed over the last three years to build a solid electoral base and provide coherent organization to the party: today they are reduced to the role of also-rans.

The only positive note, albeit tinged with bitterness, has been the commitment of people like Kan, the Premier at the time of the Fukushima disaster, to rebuilding the foundations of consensus among the grass roots, microphone in hand and standing on a beer crate.

Following the success of Abe’s 2012 campaign slogan “Nihon o torimodosu” (retake Japan) , two years on he is taking advantage of the lack of real alternatives to his premiership and his government.

“Keiki kaifuku, kono michi shika nai” Abe says in his new electoral manifesto, “there is no other road but this”.

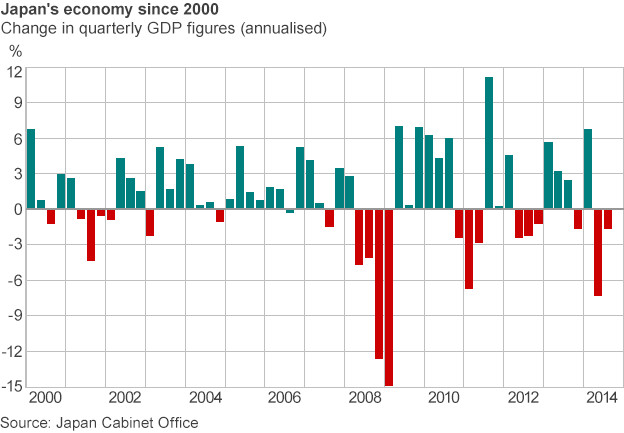

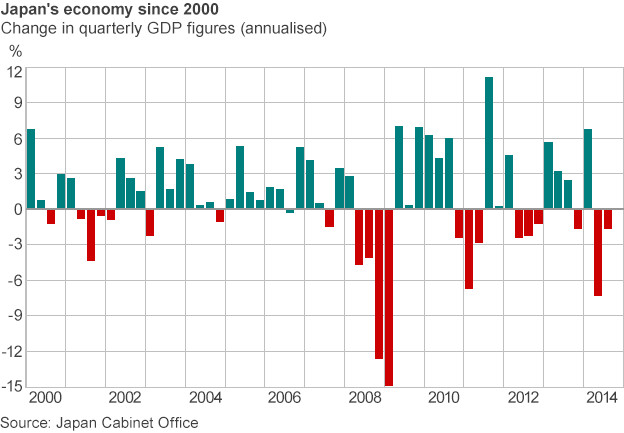

Through “Abenomics”, the aggressive economic policy based on increasing inflation and the consequent devaluation of the Yen, the Japanese Prime Minister has won admirers around the world, prompting some to propose following Japan’s example. The latest data, however, indicates that the project has hit the skids.

Instead of the expected 2% growth, the GDP of the world’s third largest economy actually contracted by 1.6% between July and September.

Partly to blame was the decision in April of this year to increase from 5% to 8% the shōhizei tax on consumption, the Japanese equivalent of VAT: this only exacerbated the trend of declining consumption. Alternatively, if last week’s declaration by Minister of Finance Tarō Asō is to be believed, the contraction is the fault of childless families and incompetent managers.

“Either you’re with us or you’re against us” seems to be Abe’s message to his followers. However, phase two of Abenomics, which Tokyo hopes will be more effective than phase one, is only a part of the LDP’s wider project; a project that, according to some close observers such as Nakano Kōichi, professor of political science at Sophia University in Tokyo, is leading Japan increasingly towards the right.

There are, in fact, two further chapters of Abe’s programme that will provide a conservative imprint to the government set to be formed in a few days’ time: firstly the educational reforms, in particular regarding history books considered too politically correct in their treatment of China and South Korea during the Japanese advance across Asia at the beginning of the twentieth century, secondly the reform of the 1947 Pacifist Constitution, which is being reinterpreted in the name of the right to collective self-defence.

Such an interpretation would, in the case of a Japanese ally being attacked, permit a military response from Japan. Some would call this war. In Tokyo they prefer another expression, “Proactive Peace Diplomacy”.

Edited by Nicholas Neiger