Newspapers have dubbed it the “water crisis”. Antonio Gramsci, in his Prison Notebooks in 1930, wrote that “the crisis consists precisely in the fact that the old is dying and the new cannot be born: in this interregnum a great variety of morbid symptoms appear”.

Iran is now in this limbo, between past and future. For years, while the land was drying up – especially in the center of the country – Tehran has focused on the cure and not enough on the disease.

Now it’s time to change gear, it’s time for a paradigm shift: by addressing the symptoms, and particularly the causes. Data is saying that, land is claiming that, economy asks for it. The country had not seen so little rainfalls for the past 47 years. And water is as the new oil for the future.

Resources distribution and new projects

A few days ago, the Tasnim agency reported that, this autumn, rainfalls have dropped by 74 percent compared to last year. Water reservoirs have almost halved. The risk is that next year (which begins on March 21st 2017 according to the Persian calendar), drinking water will be in short supply in the whole country.

Iran’s Energy Minister, Hamid Chitchian, announced a plan to divert water resources to urban centers and to reorganize agricultural and industrial supplies. “The issue of water is not merely a technical one. There are many social, economic and environmental aspects to it that altogether affect the lives of the citizens,” he admitted. Furthermore, deputy Energy Minister, Sattar Mahmoudi, told Iranian media of a research project focusing on looking for underground resources, as deep as 2000 meters, which would also involve Russia’s help.

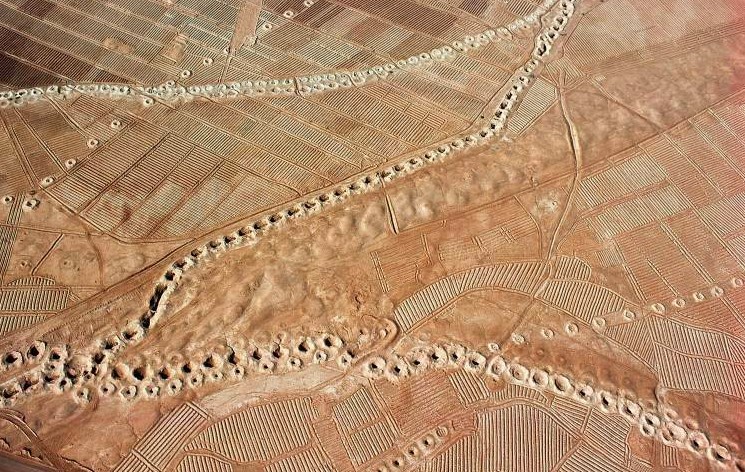

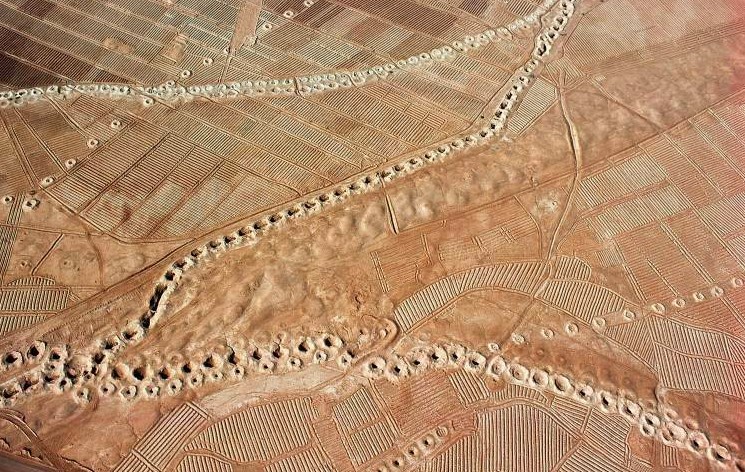

Iran has one as ancient as efficient water transport system, made up of underground tunnels and vertical structuters, called qanāt. The Shushtār historical hydraulic system in Khuzestan region, , dating back to the fifth century B.C. is in the UNESCO’s World heritage list.

Yet all this is not enough.

The lake symbol of drought and the “hydraulic mission syndrome”

In late August, the campaign “I am Lake Urmia» من_دریاچه_ارومیه_هستم# was launched on social media, requesting attention and assistance from the United Nations. Nearly two million signatures were collected. Urmia became a national emblem, with its now turned red waters: it is a salty area of 5200 km2 in northwestern Iran, which has now shrunk to 10 percent of its original size.

There are several factors that have drained Lake Urmia: 1) more than 50 dams in the area, 2) intensive irrigation activities, 3) unregulated use of water resources, 4) indiscriminate use of fertilizers.

As the researchers Shirin Hakim and Kaveh Madani argued, Iran suffers from a “hydraulic mission syndrome”, a state of mind in which one country tries to manipulate the internal water resources to meet demand through short-sighted measures based on technology and large-scale engineering.”

The origin of the crisis: population growth, inefficient agriculture and poor management

From 1979 revolution to the present day, the population has nearly doubled and moved largely from rural to urban areas. In the 1970s, 44 percent of Iranians lived in the cities, as today the percentage has risen to 70 percent. Therefore, a massive demand for water supplies concentrated in small portions of the country, without an adequate response in terms of facilities and distribution control.

If agriculture contributes to about 8 percent of GDP and employs approximately 20 percent of the population, it consumes 92 percent of Iran’s resources, while only 15 percent of the country’s area is cultivated. Overwhelmed by the international sanctions and drought, pistachios’ export decreased from 33 to 13 percent. According to Iran’s Chamber of Commerce data, 20,000 hectares of pistachio fields are drained every year due to desertification.

Behind numbers, the socio-economic situation, but also the intermittent management and shortsighted policies related to water and development quickly pushed Iran in the interregnum of a true crisis.

To conclude, Tehran does not lack technology or technique, but a more conscious and less oriented to short-term development management strategy. This will mean: first, less waste and more resources; second, a better-structured network of cooperation among different sectors related to water governance: from agriculture to transportation.

What is certain is that, continuing to exploit 97 percent of its resources (compared to 40 percent at the international level) for Iran this situation would become a “self-inflicted crisis”.