Such an unprecedented crisis has led to severe difficulties in many EU Member States and has revealed serious deficiencies in ensuring the efficient external border and in the reception and processing of arriving migrants.

The EU response to the crisis has been quite fragmented and ineffective so far. In September 2015, EU interior ministers voted by a majority a “quota plan” concerning the relocation of 160.000 migrants from Member States under extreme pressure (like Greece, Italy and Hungary) to other EU Member States on the basis of obligatory quotas. Along with the relocation, it was decided that EU agencies should staff 6 locations in Italy and 5 in Greece – the so-called “hotspots” – to identify and fingerprints migrants, lodge their asylum claims and check that they pose not security threats. After that Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary and Romania were outvoted at the ministerial meeting, some weeks later also the new Polish government opposed to the plan. Due to the mounting opposition to such a plan, only a few hundred migrants have been resettled under the scheme so far. At the same time, no significant steps forward have been made with reference to the revision of the Dublin rules.

In October the EU started to negotiate a deal with Turkey, which was closed on mid-March 2016. The EU and Turkey mainly agreed that: a) all new irregular migrants crossing from Turkey to Greece as of 20 March 2016 will be returned to Turkey; b) for every Syrian being returned to Turkey from Greece, another Syrian will be resettled to the EU; c) Turkey will take measures to prevent new routes for irregular migration from Turkey to the EU. All this will be done in return for a) the disbursement by the EU to Turkey of €3 billion followed by an additional €3 billion to be disbursed up to the end of 2018; b) an acceleration of the liberalisation of the visa requirements for Turkish citizens; c) the commitment to upgrade the Customs Union between EU and Turkey; d) the commitment to re-energise the accession process. A big question mark hangs over the real political will of the EU Member States to effectively implement this deal…

These, as the other measures agreed by the European leaders – such as the deployment of European border forces, or the adoption of emergency funding to assist migrants in EU and non-EU countries, the resettlement of migrants from non-EU countries to provide them with a safe alternative to transits with people smugglers, the improvement of procedures to return home the economic migrants whose claims for refugee status fail – have been not adequately implemented. At the same time, due to the terrorist attacks on the European soil – notably in France and Belgium – the issue of the responses to the migrant crisis is intertwined with the issue of the measures needed to face the threats of the international terrorism and ensure the security of European citizens. To this regard, much more needs to be done with reference to information-sharing between EU Member States: the reluctance of national governments to share data gathered by their police and intelligence sources is making Europe vulnerable in the fight against terrorism. At the same time, the harmonization of national legislations and the adoption of truly European ‘tools’ (such as a European Public Prosecutor) with the adequate powers and resources is crucial. Having open internal borders without having open information is not sustainable anymore.

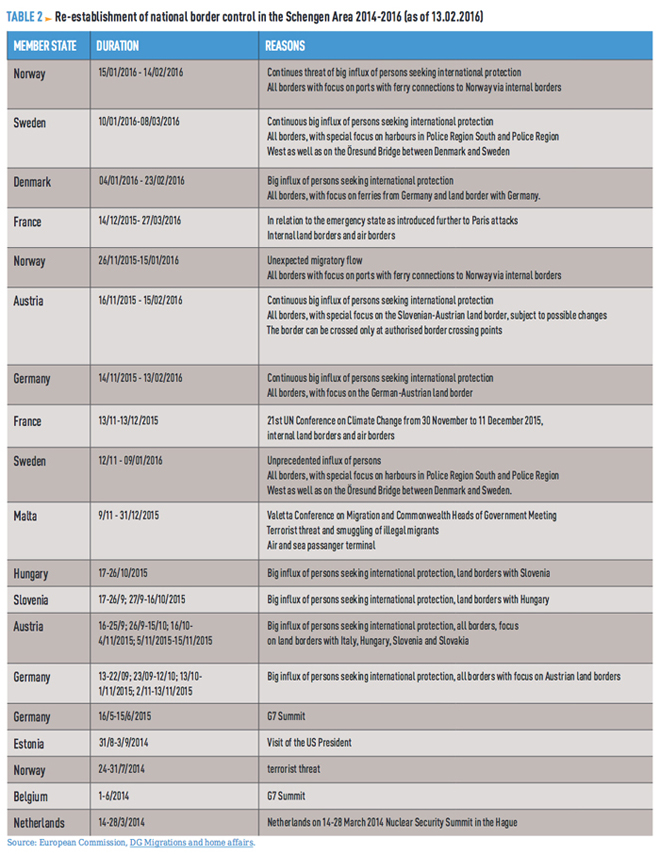

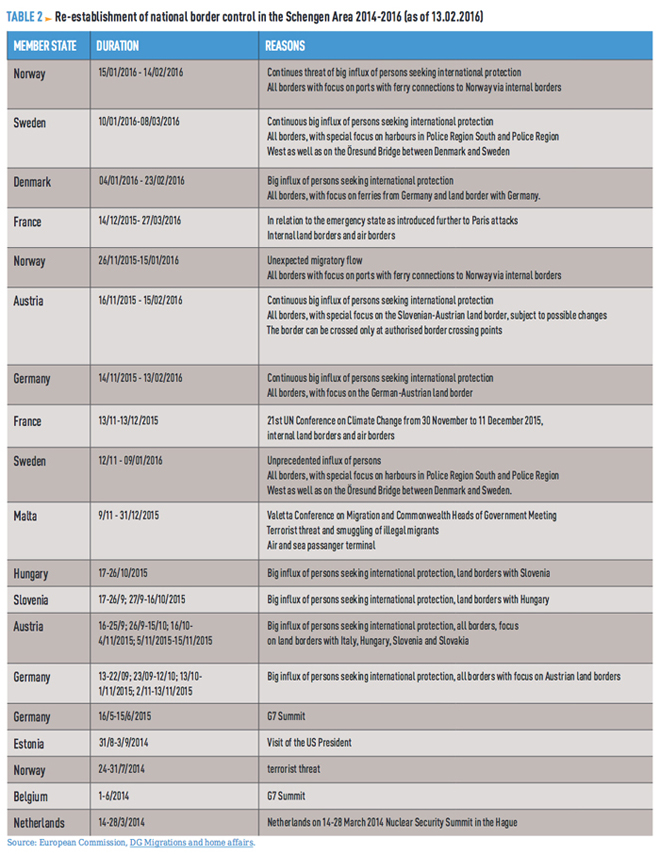

Apart from these responses at the EU level, many Member States have unilaterally decided to reintroduce temporary internal border controls: since September 2015, 8 countries have unilaterally reintroduced border controls. This kind of decision is probably the main political problem today, since it risks to: a) jeopardize the judicial and police cooperation among the Schengen countries; b) have a dramatic impact on the EU economy; c) entail economic, political and social costs d) feed populist and nationalist parties and movements all around Europe. In light of this, the perspective of a permanent reintroduction of internal border controls – which still seems very unlikely – is a nightmare not only for citizens’ rights and freedom of movement but also from an economic perspective. According to the European Commission, the reestablishment of border controls within the Schengen area would generate direct costs for the EU economy in a range between €5 and €18 billion annually. The medium term indirect costs may be considerably higher with unprecedented impact on intra-community trade, investment and mobility. According to France Stratégie, trade between countries in the Schengen zone could be reduced by at least 10% through the permanent reintroduction of internal border controls. According to the Bertelsmann Stiftung, in the case of a reintroduction of border controls, over a period of 10 years, the economic performance of the EU as a whole would be between €500 billion and €1.4 trillion lower than without such controls.

Re-establishment of national border control in the Schengen Area 2014-2016 (as of 13.12.2016)